Gloves off?

US stocks held up well during a wild week of White House adjustments to its tariff policies. US government bonds and the dollar were less fortunate.

With stocks plummeting and the bond market “getting a bit yippy”, the White House paused most of its ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on Wednesday last week. While President Donald Trump appears a little too nonchalant, this is evidence that he is mindful of the market, at least.

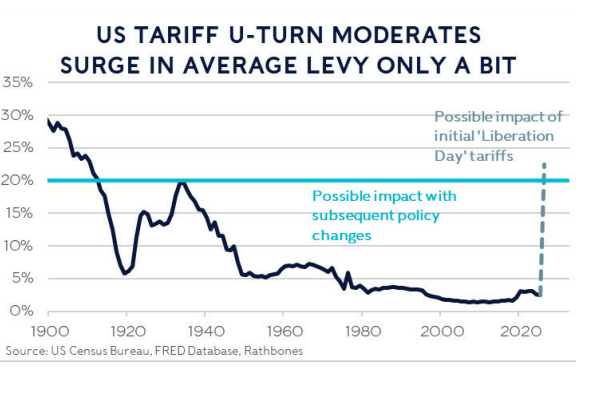

US stocks rallied 5.7% in dollar terms last week, albeit they are still down 8.5% year to date. While the more punitive reciprocal tariffs have been paused for three months to allow negotiations, those levied on Chinese imports were increased in a rapid tit-for-tat that has left Chinese exports to America taxed at 145% and US exports to China at 125%. Also, the 10% universal tariff on all other imports remains in place. While stock investors have taken heart from the reprieve, it is very limited. As you can see from the chart, we estimate the average tariff on imports to America is as high as at the end of the 1930s.

We haven’t included the potential effect of the weekend’s announcement that computer chips, smartphones and computers are exempt from the ‘reciprocal’ tariffs. Which is good, because the administration has already clarified that somewhat (but not a lot, as is their style): US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said these products would instead be subject to tariffs under a different regime solely for high-end electronics that will be revealed in due course. There’s a high chance that this tariff will be at a lower rate than the 145%, and many investors expect substantially lower. We’ll have to wait and see. And see how the opening gambit changes over time, as it is wont to do … So why did Trump relent and pause the tariffs at the last minute? It seems the government bond market was what really got him and his staff worried. Longer-term US treasury bond prices dropped like stones, sending their yields – and therefore government borrowing costs – soaring. While the level isn’t necessarily that high compared with the last year or so, the size and speed of the increase in such a short space of time was extraordinary.

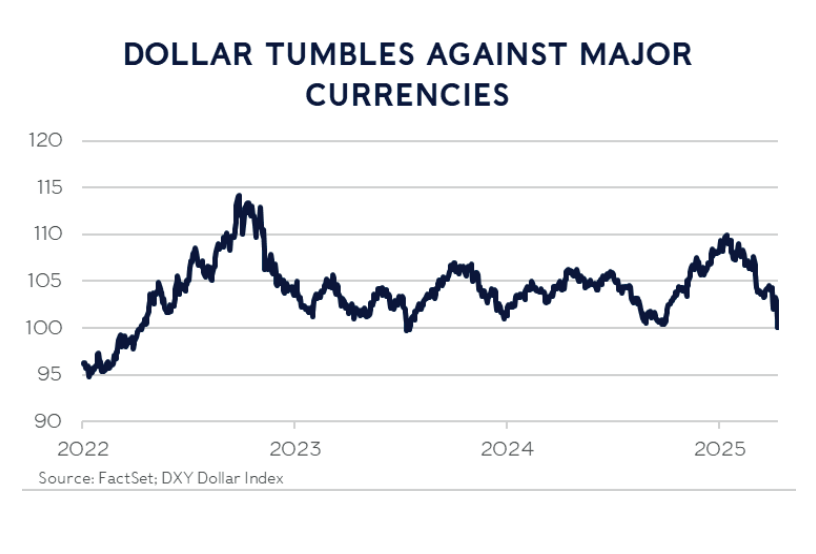

At the same time, the dollar sank significantly as well. After a dreadful run, the greenback is now 9% cheaper against its major trading partners than its recent peak in mid-January. Typically, when American government bond yields rise, the dollar strengthens as it attracts global investors who want to lock in higher ‘risk-free’ returns. This is the mechanism that allows the US to spend beyond its means and to borrow with abandon in ways that are impossible for nations like the UK. Last week, small cracks began to show in this arrangement.

High borrowing costs could cause misgivings in the Republican-led Congress, which is currently debating hefty tax cuts. The House of Representatives have passed a detail-lite plan for $5 trillion in tax cuts and $1.5trn in spending cuts over the coming decade. It must be combined with a Senate version, however, which requires a minimum of $4trn in belt-tightening.

This isn’t the 1930s

The administration’s sensitivity to economic reality is comforting, even if their modus operandi is still shock, awe and uncertainty – not a helpful mix for investors and business.

It’s important to remember, though, that trade policy isn’t all that matters for business and investment. People and companies are adaptive and can adjust their suppliers, business models and strategies. While we may look back on 2025 as the start of a huge realignment in global trade, it’s not going to be the year where companies stopped making profits.

This isn’t the first major shock to economies and markets. It’s not even the first in the past five years! In 2020 a pandemic completely upended life and commerce in virtually every nation. Everything came to a standstill. Yet societies and business adapted and in many cases thrived. Two years later, Russia invaded Ukraine, completely scrambling markets for everything from grains and plutonium to oil and gas. All economic growth is essentially energy transformed, so skyrocketing energy costs (and food, which is energy for workers) was a massive shock, yet economic activity adapted and continued.

In both those years, 2020 and 2022, global stocks experienced falls of more than the 19% we’ve seen so far this year. Both times they bounced back. This isn’t unusual: since 1960, 92% of rolling 10-year periods have been positive.

Some people compare today with the Great Depression of the 1930s, worrying that history will repeat. This is a misreading of history. The Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 didn’t create the Great Depression – it made it a little worse, but it wasn’t the trigger or the main driver. It was implemented during perhaps the greatest banking crisis of all time. Back then, currencies were convertible to gold, making it harder for central banks to alleviate stresses and help reinvigorate commerce and economies. This is not remotely like the situation we find ourselves in today.

The value of currencies float, allowing them to find an equilibrium without causing massive layoffs or requiring big cuts in workers’ wages. Central banks have a whole range of tools to monitor banks and compel them to rein in lending or raise capital. They can also intervene in markets to increase ‘liquidity’ (make it easier to sell quality assets in times of dislocation), keeping panic spikes in borrowing costs from upending those who would otherwise be solvent. Despite wild trading and the big moves in the prices of bonds and equities, there are no signs of stress in banks or financial conditions. Given the tools they have at their disposal, central banks have never been better placed to avert or contain a financial crisis. And such a crisis is the major risk to long-term investors.

While the effect of tariffs – if they go ahead in the form that’s currently on hiatus – will mean a big knock to US GDP growth, they don’t guarantee recession. We calculate the chance of a US recession to be roughly 35%, i.e. it’s more likely than not that America will continue to forge ahead in the year to come. That’s important because it’s recessions that tend to deliver large and lasting stock market slumps.

There’s always a tendency to focus too much on the risks of our endeavours and not on the potential rewards. We’re human: it’s a biological coding that makes us more concerned about losing what we have than choosing the unknown that could provide more. But for those who can invest for five to 10 years, history shows it’s best to play the long game.

The views in this update are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions and are current as of the date posted. While all material is deemed to be reliable, accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed.

This document was originally published by Rathbone Investment Management Limited. Any views and opinions are those of the author, and coverage of any assets in no way reflects an investment recommendation. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and you may not get back your original investment. Fluctuations in exchange rates may increase or decrease the return on investments denominated in a foreign currency. Commissions, trailing commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with mutual fund investments. Please read the prospectus before investing. Mutual funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated.

Certain statements in this document are forward-looking. Forward-looking statements (“FLS”) are statements that are predictive in nature, depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “could,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “plan,” “believe,” or “estimate,” or other similar expressions. Statements that look forward in time or include anything other than historical information are subject to risks and uncertainties, and actual results, actions or events could differ materially from those set forth in the FLS. FLS are not guarantees of future performance and are by their nature based on numerous assumptions. The reader is cautioned to consider the FLS carefully and not to place undue reliance on FLS. Unless required by applicable law, it is not undertaken, and specifically disclaimed that there is any intention or obligation to update or revise FLS, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.