Tax Treatment of Distributions

Generally, you can shelter investment income from tax inside either an RRSP – where tax can be deferred until you take out the money – or through a TFSA, where the growth and income is tax free even when you do decide to withdraw it.

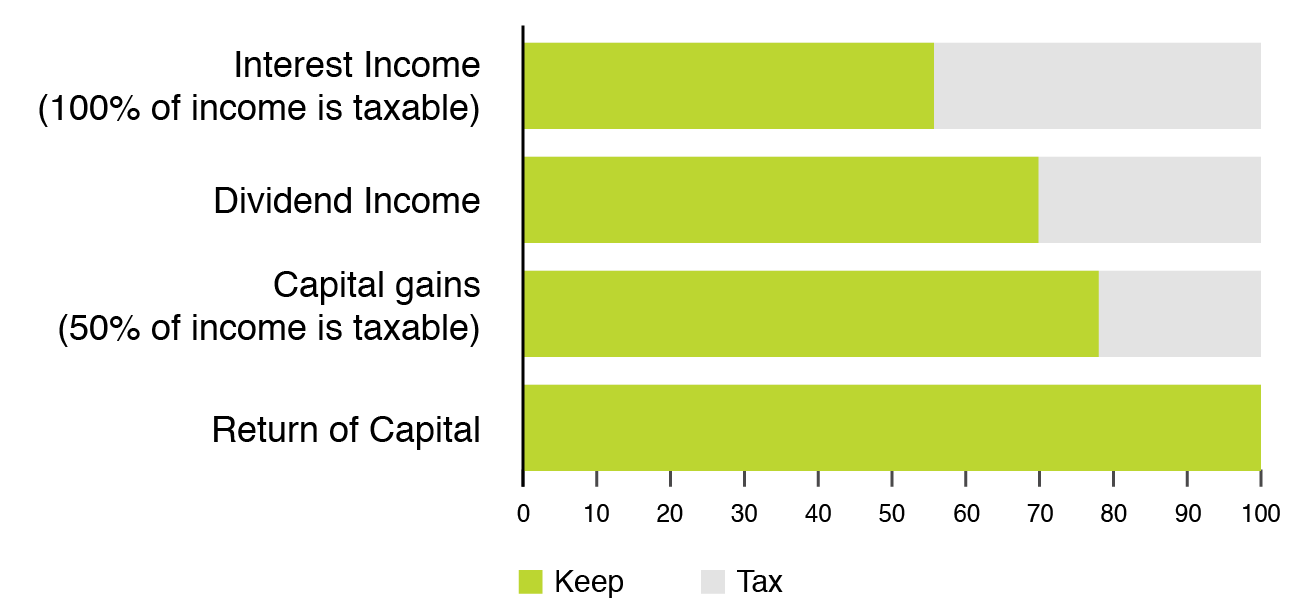

Once you have reached your annual RRSP and TFSA contribution maximums, you can use non-registered accounts, where investment income and gains will be subject to tax. The amount of tax depends on the province in which you live, the income you earn and most importantly, the type of investment income you receive.

The good thing is that not all investment income is taxed equally.

Distributions are a source of income paid out by mutual funds and are generally made up of earnings generated by the different types of investments held in the fund.

There can be five sources of income, and each is taxed differently:

Tax Treatment of Distributions

For illustrative purposes. Based on top marginal tax rate for Ontario in 2015 at 49.53%. Tax credits differ from province to province.

1. Interest Income

Products such as guaranteed investment certificates (GICs), high-interest savings accounts and bonds generate interest earned from debt. Any interest income you earn is fully taxable based on your marginal income tax rate. So, for most investors, it makes sense to hold investments that generate this type of income in a tax-sheltered account.

2. Dividends

Dividends represent a distribution of a company’s earnings to shareholders. “Eligible” dividends from a taxable Canadian corporation receive enhanced federal and provincial dividend tax credits, which reduce the amount of tax owing.

Treatment of U.S. Dividends for Canadians

The Canada/U.S. tax treaty* allows investors to avoid a 15% dividend withholding tax if they hold U.S. dividend-paying investments in a registered retirement account like an RRSP or RRIF. However, this exemption does not apply to TFSAs or RESPs since they are not considered retirement accounts.

Some dividends are not considered “eligible” for tax credits – such as those paid by U.S. corporations – and are taxed at your marginal income tax rate.

3. Capital Gains

If you sell an investment in a non-registered account for more than you paid for it, you have made a capital gain. When it comes time to pay taxes, you only pay tax on 50% of the gain. For example, if you invested $20,000 in a mutual fund and sold it for $30,000, you would declare a $10,000 capital gain in the year you sold. With the capital gains inclusion rate at 50%, you would only include $5,000 in your total taxable income.

4. Foreign-Investment Income

Interest, dividends or capital gains that stem from investments from non-Canadian sources must be reported in equivalent Canadian dollar values. They do not qualify for dividend tax credits and may be subject to withholding tax. However, a foreign tax credit may be available to prevent double taxation.

5. Return on Capital (ROC)

Mutual funds that pay a fixed monthly distribution are most likely to have this type of distribution. It’s a payment from the capital of the fund that is generally not taxable. It can, however, reduce the investor’s adjusted cost base (ACB), increasing the capital gain or decreasing the capital loss on the investment when sold. Funds that include ROC in their distributions are ideal for investors who want a predictable stream of income from their investments.

Good ROC vs. Bad

There are different kinds of ROC that investments can distribute. Some are not always beneficial to investors. The ROC described in point #5 is an example of good ROC. So what is considered bad ROC?

Sometimes, mutual funds distribute a portion of the investor’s original capital back in the form of ROC. This might occur if a fund is not generating enough income or gains from its holdings to meet its fixed distribution obligation to investors. This type of ROC could potentially create a taxable capital gain when you sell the investment even if it didn’t increase in value.

If you have any questions regarding distributions and tax implications, please contact your financial advisor and/or consult with a qualified tax specialist.

*Source: Department of Finance, Government of Canada