France cuts spending, ecb to cut rates?

THE TWIN ENGINES OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMY, GERMANY AND FRANCE, ARE SPUTTERING. WITH INFLATION FALLING AND FRANCE TURNING TO AUSTERITY, WILL THE CENTRAL BANK COME TO THE RESCUE?

Europe had a tough summer. Well, that’s not quite true. Parts of Europe have done very well indeed – particularly tourism hotspots in the Mediterranean making hay off record levels of visitors, especially flush Americans.

But the big driver of European growth is northern Europe: especially Germany and France. These two economies are by far the largest in the EU and it’s their fortunes that tend to determine the fate of the Continent. And lately, they haven’t been doing so well. Germany’s GDP growth has been rocky, swinging from small expansion to contraction and back again. In France growth is better, yet steadily fading. And that’s with the government splurging money hand over fist – it’s currently spending more than it receives in taxes to the tune of 5.5% of its GDP. EU rules cap this ‘deficit’ that member nations can run at 3% of GDP (outside of unusual circumstances, such as the pandemic). Germany has managed to reduce its deficit spending to 2.5%, but that’s squeezed GDP growth. Weakness in China, a big export market for German (and other European) manufacturers, hasn’t helped either.

France faced fiscal reality last week and announced a form of austerity (sharp reductions in government spending and entitlements, like pensions) and heavier taxes on the wealthy and businesses. These measures are forecast to improve the government’s receipts relative to spending by roughly 2% of GDP. This is broadly the same magnitude as the ‘political turn’ of left-wing President Francois Mitterrand back in 1983 when he capitulated to the reality of unaffordable policies. While this should help restore credibility and fiscal rigour to France, it will cause economic pain and reduce both its own GDP growth and that of the EU as a whole.

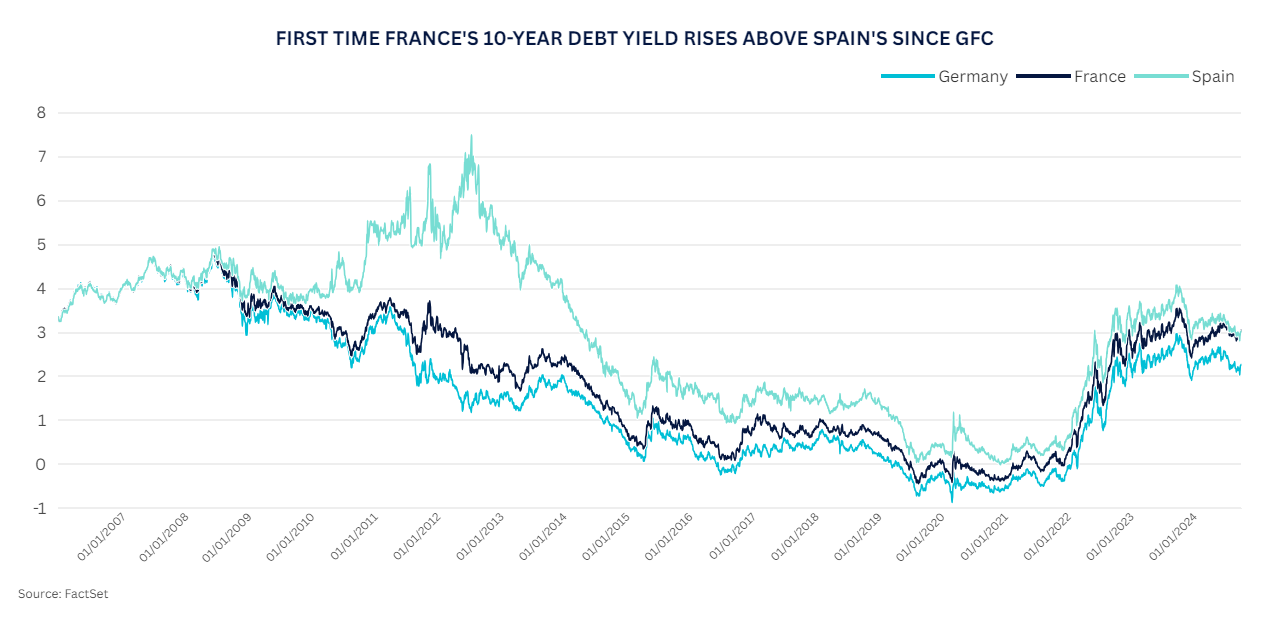

Despite this drastic action, rating agency Fitch put France on a negative outlook, which means it’s pondering downgrading the nation’s AA- credit quality. Investors have also weighed in: last week the yield of the benchmark French 10-year government bond rose above that of Spain for the first time since the Global Financial Crisis.

With fiscal policies becoming more restrictive on economic growth, eyes turn to monetary policy – the European Central Bank (ECB) – to help reduce the pressure on governments, households and businesses. Euro Area inflation fell sharply in August and September, first to 2.2% and then to 1.8%.

This represents both a potential symptom of the economic difficulty unfolding on the Continent and an opportunity for the ECB to cut interest rates. The ECB is expected to cut rates by another quarter-percentage-point when it meets on Thursday. That would be its third cut this year, taking the rate to 3.25%.

US election too close to call

As the US election speeds towards us, the two candidates remain neck and neck according to betting odds on PredictIt, a not-for-profit political betting site. Yet polling in the battleground swing states shows Republican Donald Trump has increased his lead over Democrat Kamala Harris in recent weeks.

While the economic policies of both sides are actually more alike than either would wish to admit – protectionist and loose with government cash – there are stark differences that do matter for investors. Mostly, this is down to differences in scale, as both candidates talk tough on trade and immigration.

Trump has suggested a ‘universal tariff’ on all imports at between 10-20% (it changes often) and a bumper tariff of 60% or so on Chinese products. The average tariff on imports to the US has been firmly below 4% since the 1970s. If followed through, this increase would set a fire under inflation. As would Trump’s planned crackdown on immigration – he has said he would deport all undocumented immigrants in the country and greatly curtail the number arriving legally (last time he was President, it fell by about 50%). The presence of fewer workers would bid up wages; more expensive imports would raise costs and reduce choice (and therefore price competition) for households and businesses alike. Trump also plans to deregulate business, particularly relating to the environment, and reduce subsidies for clean power. Harris would more than likely retain the status quo on all these issues, although lately she’s talking tougher on immigration and Chinese imports.

Another big difference is with plans for the corporate tax rate. Trump’s official platform says he intends to keep the rate at 21%, the rate he cut it to in 2017 when he was President. But he has mulled cutting it even further to 15%. Meanwhile, Harris has pledged to raise the rate to 28%. For an American company paying the headline rate of tax, a cut to 15% would boost profits by 8%, while an increase to 28% would reduce profits by 9%. That’s roughly equivalent to an average year’s earnings growth either gained or lost. This is a big swing for potential profits – and one depending on an uncertain election.

Whether Harris or Trump wins the White House is too close to call. As is the fight over Congress. It won’t take much for Republicans to overwhelm the Democrats’ razor-thin majority in the Senate, yet their own hold on the House of Representatives is extremely slim. A switch in control of both chambers of a divided Congress has never happened before. It may just occur this November. A split Congress would make it difficult for whoever wins to implement their agenda. Often not necessarily a bad thing!

One thing both presidential candidates agree on is spending more money than they get in taxes. That means the amount of US Treasury bonds issued is likely to keep rising, which could put upward pressure on their yields. Any resurgence of inflation would have a similar effect. We think the chances of inflation heading higher are low, but it’s something to keep an eye on.

The views in this update are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions and are current as of the date posted. While all material is deemed to be reliable, accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed.

This document was originally published by Rathbone Investment Management Limited. Any views and opinions are those of the author, and coverage of any assets in no way reflects an investment recommendation. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and you may not get back your original investment. Fluctuations in exchange rates may increase or decrease the return on investments denominated in a foreign currency. Commissions, trailing commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with mutual fund investments. Please read the prospectus before investing. Mutual funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently, and past performance may not be repeated.

Certain statements in this document are forward-looking. Forward-looking statements (“FLS”) are statements that are predictive in nature, depend upon or refer to future events or conditions, or that include words such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “could,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “plan,” “believe,” or “estimate,” or other similar expressions. Statements that look forward in time or include anything other than historical information are subject to risks and uncertainties, and actual results, actions or events could differ materially from those set forth in the FLS. FLS are not guarantees of future performance and are by their nature based on numerous assumptions. The reader is cautioned to consider the FLS carefully and not to place undue reliance on FLS. Unless required by applicable law, it is not undertaken, and specifically disclaimed that there is any intention or obligation to update or revise FLS, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.